A Brief History Boats on the Coast of North Carolina

Shapie schooners at beaufort

The history of coastal North Carolina from the Colonial Period to the post World War II era is centered on boats. Maritime transportation routes were key in conveying people, things, and ideas from one place to another — all by boat. Much attention has focused on North Carolina’s “Graveyard of the Atlantic” and lifesaving, shipwrecks, and military activity in ocean waters. Less widely known is the rich history of trade, civic, and kin relationships that extended across the sounds of North Carolina from Shackleford Banks, Core Banks, Portsmouth Island, Ocracoke, and Hatteras Island to mainland ports such as Elizabeth City, Edenton, Bath, Washington, New Bern, and Beaufort.

Before the construction of bridges and paved roads, barrier island communities of North Carolina were considered isolated if not “backward.” One document, for example, described pre-1960s banks dwellers as “isolated from the rest of the country” and “separated by their own peculiarities.” Yet upon closer inspection the waterbodies that lay between barrier islands and the mainland comprised an intricate network of transportation routes, carved around sloughs, channels, inlets, and shoals.

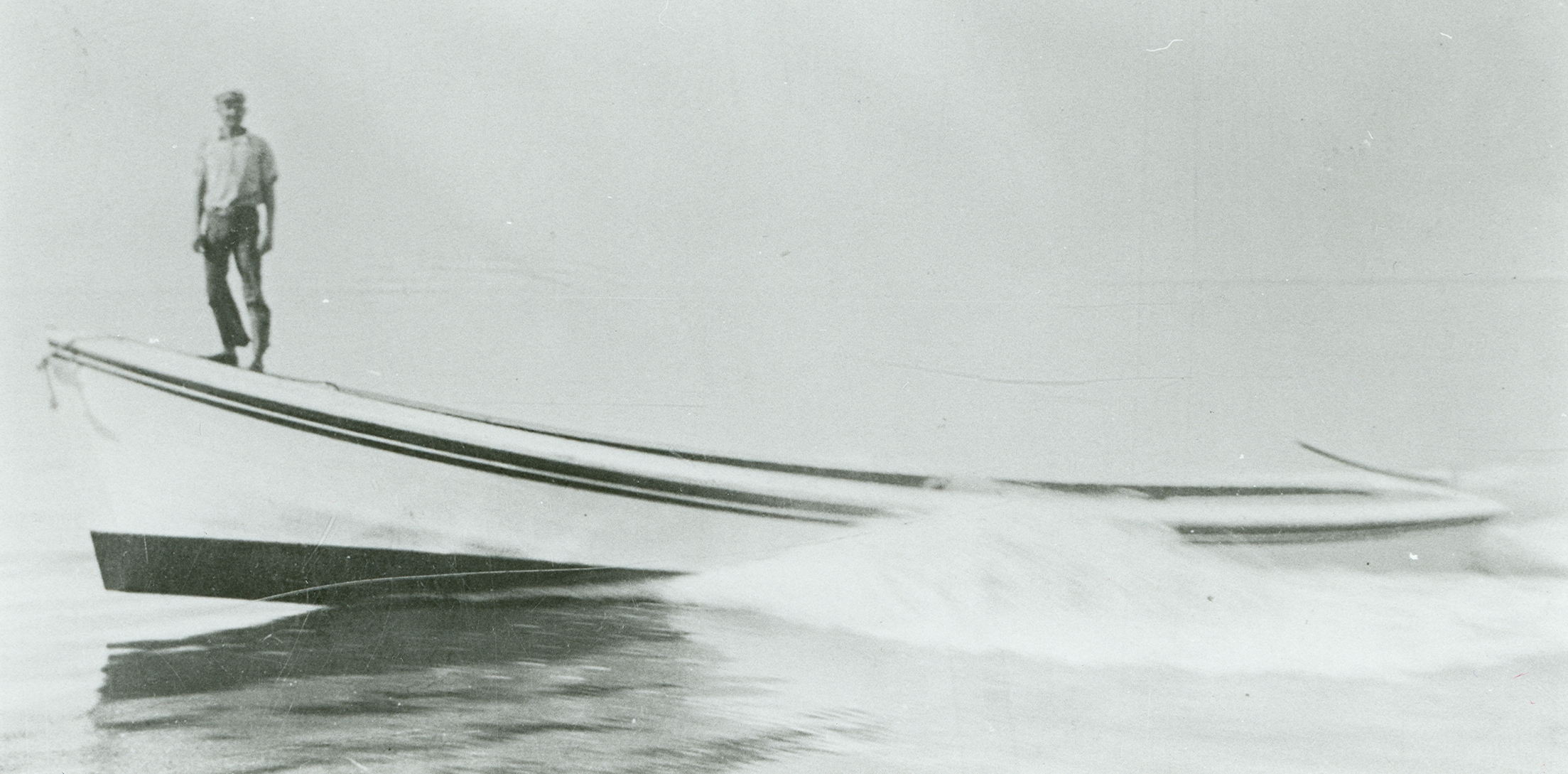

Devine Guthrie

Powered Shad Boat

Early bankers from Hatteras to Shackleford played an important role transporting goods such as whale oil, salted fish, cattle hides, wool, and lumber to mainland ports. People working at lifesaving stations, light houses, schools and churches on the banks were often from the mainland. Communities were stitched together by daily mail and freight boat routes. Barrier island people were connected to the mainland and to American history by way of boat.

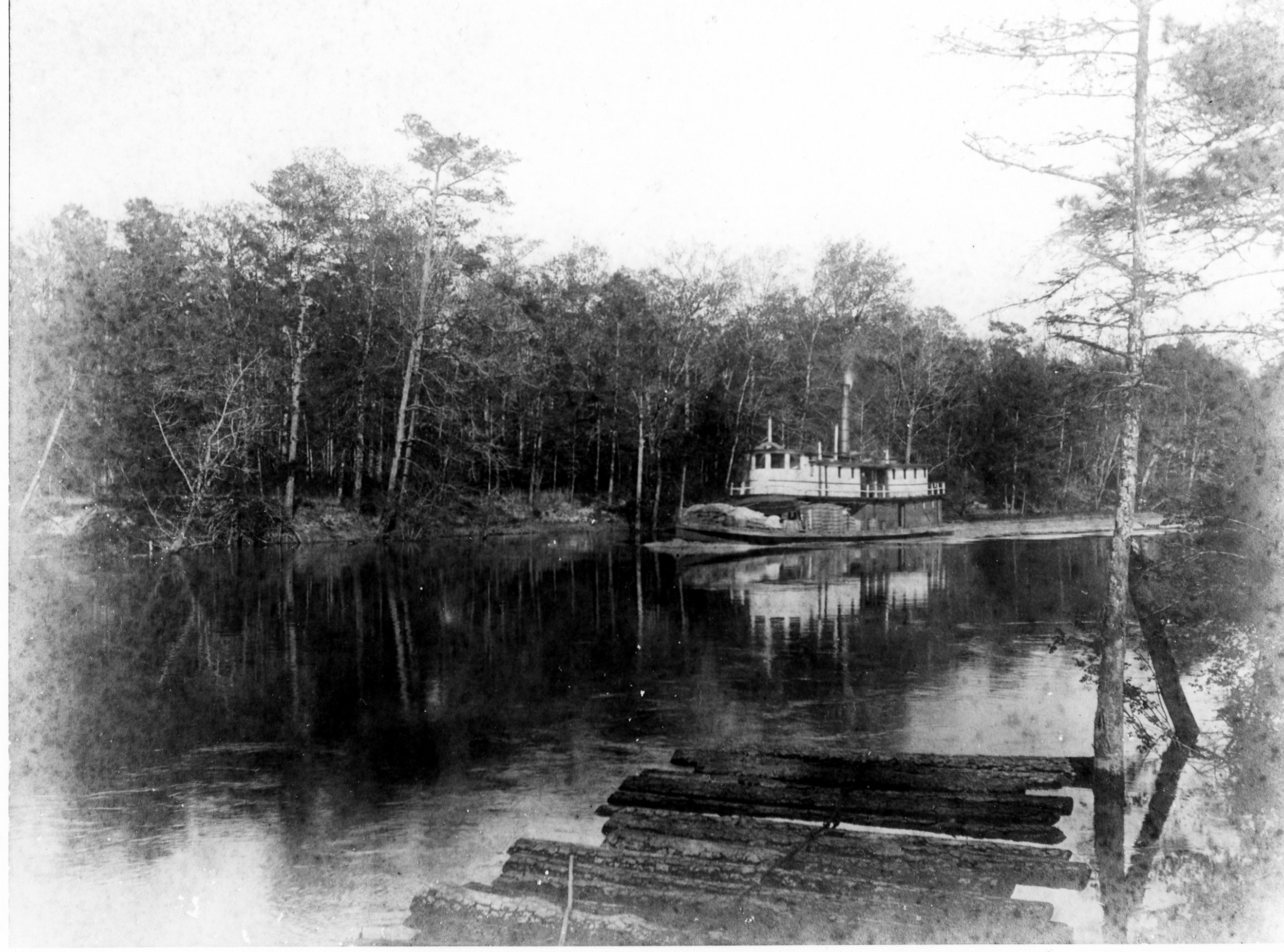

Steamboat on Tarboro

Steamboats: Steamboats, propelled by steam power, carried freight and passengers from port to port along North Carolina's sounds and rivers. Steamboat travel became popular in the early 1800s until the late 1930s. Early maps show stagecoach routes connecting to steamboat ports. As the railroad system expanded, train companies worked in conjunction with steamboats, although eventually causing their demise. An advertisement for the Norfolk Southern Railroad, for example, listed the steamer Plymouth as making daily departures from Edenton to Plymouth, Windsor, Lewiston, and Tarboro, returning in time to connect with the mail train for Norfolk.

Steamboat Greenville on the Tar river

Steamboats navigated impressive distances westward up the rivers of North Carolina. They ran the Neuse River from New Bern to Kinston and even Smithfield, near Raleigh. They ran the Trent River from New Bern to Pollocksville and Trenton, and then to Hookerton and Snow Hill via Contentnea Creek. Weldon was the upper Terminus on the Roanoke River for Steamboats departing from Plymouth. Steamboats traveled north to Norfolk by way of the Dismal Swamp Canal, the oldest surviving waterway in continuous use in the United States.

Steamboats include the Luray, Neuse, Ocracoke, and Albemarle, owned by the Old Dominion Steamship Company and Norfolk Southern Railroad. They steamed from New Bern to Elizabeth City, Manteo, Roanoke Island, and Oriental on a daily basis. The Alma is a steamboat featured in Port Light. Although most American showboats were powered by steam, Port Light's James Adams Floating Theatre was not a steamboat, but a barge towed by tug boats.

Freight Boats: Freight boats were typically wooden sailing schooners, sharpies, and sloops, although steamboats were also used to transport goods. Freight boats were ubiquitous on the North Carolina coast during the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. They sailed from the Outer Banks and nearby mainland ports to New Bern, Washington, Engelhard, Elizabeth City, and Norfolk. Cargo included fish, ice, agricultural products, livestock, lumber, nails, shingles, and general merchandise.

Freight boats were shallow-drafted to navigate the shoals and shallows of Albemarle, Pamlico, and Core sounds. Until closed by storm in 1846, Ocracoke Inlet was the principal route to and from the trans-Atlantic shipping lane. Larger ships transferred their cargo at Portsmouth to smaller freight boats in a process known as "lightering." Free and enslaved watermen piloted, lightered, and sailed vessels to mainland ports.

schooner

W.M. Webb Freight boat converted to menhaden vessel

Sharpie Schooner Iowa

Sister vessel to missouri

Freight boats were multi-use, carrying passengers, fresh fish, mail, or even automobiles. When the menhaden fishery expanded, some freight boats were converted to menhaden fishing vessels. The menhaden fishmeal and oil industry, depending heavily on African-American crews, was a critical economic engine in North Carolina, especially from the 1920s through the early 1970s.

Once gas engines were introduced around 1915, freight boats were converted to power. Freight boats featured in Port Light include the Alphonso, Bessie Virginia, Hadeco, Hattie Creef, Julia Bell, and Missouri. They began to fall into disuse after road and bridge projects expanded in the 1930s.

Fish Buy Boats: Buy boat captains met fishing boats offshore or in far-flung villages and purchased fish, allowing crews to keep working without having to run several hours to the packing house. Buy boats in northeast NC went to fishing villages such as Stumpy Point and Rodanthe to bid on the day's catch. The buy boat then hauled the fish to Globe Fish Company in Elizabeth City.

The use of buy boats was prevalent in the long-haul fishery of Core and Pamlico Sound. Long haul crews would leave their home ports for several days at a time. In the communities of Atlantic and Cedar Island, buy boats serving long haul crews have evolved into "run boats," as they transport fish from the fishing grounds to the packing house, and fishermen settle up with the dealer later. A fish buy boat featured in Port Light is the Hattie Creef, and a featured run boat is the Linda.

Bailing the FisH

Credit: Lawrence S. Earley

Handling Bunt Stake

CREDIT: LAWRENCE S. EARLEY

Mail Boats: The U.S. Postal Service established service from Craven County to Carteret County, including stops in the barrier island communities of Portsmouth and Ocracoke, by 1840 (Ocracoke was part of Carteret County until transferred to Hyde County in 1845). Postal service was extended from Currituck, Hyde, and Tyrrell Counties into Dare County, including Hatteras Island, in 1870.

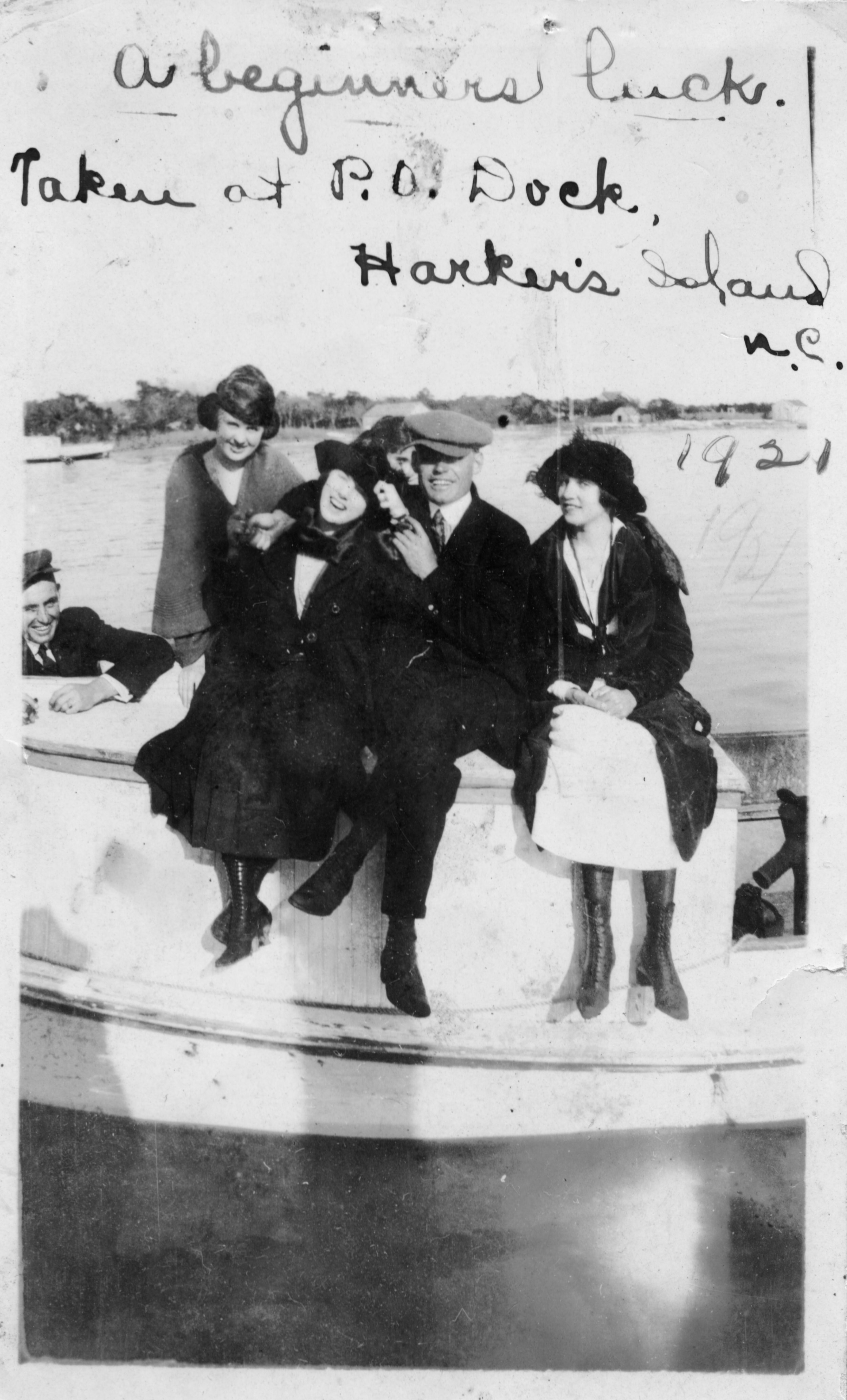

It was thus necessary to use water transportation to deliver the mail. Post offices were established along the banks, bringing about new names for many communities. For example, Kinnakeet became Avon, and North Chicamacomico became Rodanthe. Mail boat routes were mapped out, and the government awarded four-year contracts to local mariners to deliver the mail.

Mail was delivered via sailboat during the early years, typically sloops or two-masted schooners known as bugeyes. After the turn of the century gas motors began supplementing sail power. Mail boats were often modified freight or fishing boats, with a cabin for passengers, performing double-duty in transporting just about anything in addition to the mail.

Although mail boats are still used in Maine and other areas with island communities, the service ceased in coastal North Carolina by 1964 with improvements in roads, bridges, and the ferry system. Mail boats featured in Port Lights are the Aleta and Virginia Dare.

Dare County Mailboat Routes

Mailboat Dock Pickup

Friends at Dock

Gloucester Landing

Ferries: The first ferries shuttling people and cars to the Outer Banks were privately-owned and operated. They evolved from freight boats, which would carry everything from people and livestock to cars. Early private ferries crossed relatively short yet potentially treacherous inlets like Oregon Inlet and Hatteras Inlet. They were typically within view of the other shore, where customers could raise a flag to beckon the on-demand ferry before operators went to a regular schedule.

The North Carolina Highway Commission began subsidizing private ferry operators in the 1930s, and by the 1950s had purchased the service to begin a state ferry transportation system. The first state route linked Manns Harbor and Roanoke Island.

Disembarking Frazier Peele

A ferry service ran between Gloucester and Harkers Island in Carteret County, including the vessel Joyland. This route became defunct with the construction of a bridge in 1939. The ferry Sea Level, owned by the Taylor brothers of Sea Level, ran from Atlantic to Ocracoke beginning in 1960. It was purchased by the state in 1964, and the service was soon after moved from Atlantic to Cedar Island.

Wanchese fisherman Toby Tillett carried cars across Oregon Inlet by barge and later the ferry Oregon Inlet and the Barcelona until the state purchased the service in 1950. Frazier Peele of Hatteras established the first service to Ocracoke across Hatteras Inlet. Early ferries had the capacity to carry three or four cars, and dropped a ramp for cars to disembark, sometimes into shallow water. On Hatteras Island the Midgett Brothers ran the Manteo-Hatteras bus line which made use of the ferries. The ferry Barcelona is featured on Port Light.

Historical Timeline

1743 Ocracoke officially settled as “Pilot Town”

1753 Portsmouth officially settled as lightering port

1827 Dismal Swamp Canal opens

1834 Stage Coach route from New Bern to Beaufort established

1840 First Post Offices established on banks

1846 Oregon and Hatteras Inlets cut by storm

1859 Chesapeake and Albemarle Canal opens

1924 Toby Tillet's ferry service established across Oregon Inlet

1936 Cedar Island bridge built

1937 Manteo – Hatteras bus line begins

1941 Harkers Island bridge opens

1953 State ferry system and road paving projects begin

1957 State-owned Hatteras - Ocracoke ferry established

1961 State-owned Cedar Island – Ocracoke ferry established

1963 Herbert C. Bonner Bridge opens connecting Hatteras Island to mainland

1964 Mail boat service to Ocracoke terminated, end of mail boat era

Sources:

The Waterman's Song: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina. David S. Cecelski, University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

The Workboats of Core Sound. Lawrence S. Earley, University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

The Fish Factory. B. Garrity-Blake, University of Tennessee Press, 1994.

Ocracoke Post Office: A History of the United States Post Office at Ocracoke. Phillip Howard, Village Craftsmen Newsletter, April 21, 2013

Carolina Riverboats and Rivers: the Old Days. Earl White, River Road Publishing, Denver, NC 2002.

Postal History Project. North Carolina State Archives.